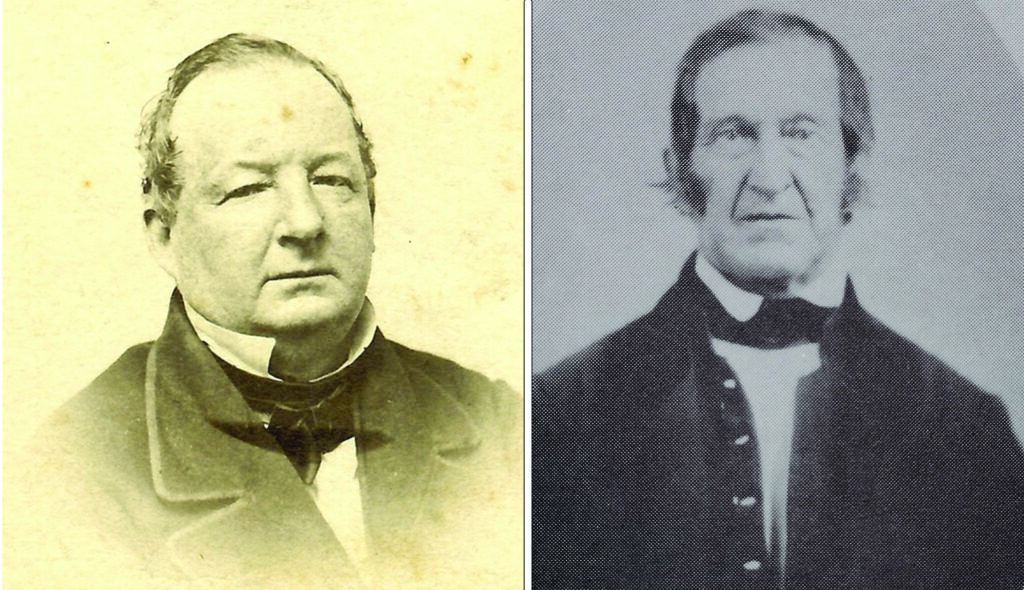

Enos Hawley was a local tanner and postmaster in Muncy who died at 84 in 1881. He is interred at the Muncy Cemetery with a rectangular stone that simply states his name and his date of birth and death – “June 10, 1799” and “Oct. 3, 1882.”

In their 2003 book “Williamsport: Boomtown on the Susquehanna,” Robin Van Auken and Louis E. Hunsinger Jr., described Hawley as being “not shy about his revulsion” of slavery.

On one April night in 1842, he was the center of a riot in Muncy. He, and several Quakers, had invited an orator to speak about the abolition of slaves.

Some locals reacted angrily and forced the speaker and audience members to Hawley’s house, where they hid from their attackers. In the aftermath, 18 men would be arrested for their involvement.

An account of this incident could be found in the local history publication, Now and Then (specifically volume 7 page 29 printed in 1942). It was originally shared by local lawyer Marshall Reid Anspach.

He had received word of an indictment of those 18 individuals. Anspach then spent “a great many hours” where he was able to locate several documents related to the incident. Yet, when he searched through the Muncy Luminary of that year, he was unable to find any mention of it.

“I failed to find so much as a single word concerning the matter. It seemed as though the subject was too hot a political potato for the paper even to mention,” Anspach said.

However, thanks to more research Anspach was able to piece together an account.

The riot

Nine of the 18 persons listed were: James Merrill, Thomas Harlan, Samuel Doctor, Jr., William Risk, Nathaniel Smith, Henry Antes, Jonathan Willetts, Thomas Brass and Robert Ray. Each of them had stoned the schoolhouse where the lecture occurred. It broke out the windows, struck the lecturer and Hawley.

At this point in the narrative of the incident, Abraham Updegraff served as a member of the jury that heard the trial. He wrote about his experience in a memoir about his father called “Sketch of the Life of the Late Thomas Updegraff.”

Thomas Updegraff described how the speaker, Hawley, and the meeting attendees fled, the 18 had “thrown baskets full of eggs” thus “bespattering them.”

After reaching Hawley’s home, the rioters “made violent assaults on the doors and windows of the house.” They also harassed the abolitionists with gong and banged it at the front of the house “until after midnight” … “while using all kinds of abusive language coupled by threats.”

The trial

Eventually, they were caught and indicted in August of 1842. They were sent to trial in September and October. The prosecution was able to produce witnesses and evidence.

“A number of witnesses were examined by the Commonwealth, all telling the same story, without variations,” Anspach said.

Yet the defense “produced no witnesses” and “made long, frothy speeches.” The defense charged that the Quakers were “active in stirring up the worst passions of the slaves in the Southern States.”

The lawyers for 18 went so far as to say the slaves “would be happy, smooth, fat, and sleek never dreaming…for liberty.” They added that “if it (freedom) could be obtained,” that the slaves “were not capable of enjoying it.”

Updegraff said the lawyers for the 18 called the abolitionists “poisonous asps, stinging the body politic to death.”

Upon hearing these remarks, F.C. Campbell, who served as a lawyer for the Commonwealth, said that between the proof of the prosecution and the “frothy” speech the defense’s lawyers gave, a closing statement was not needed.

The jury was then given the case, but upon sitting down and casting the first ballots, it resulted in “ELEVEN for acquittal…and ONE for conviction.”

Upon being questioned, it was Updegraff who voted for their conviction.

“You are a young man and you can’t expect eleven of us to yield our views of right to yours,” the foreman said.

Updegraff responded, “If the learned judge had instructed us that if we believed the evidence we must convict, and there was no contradictory evidence offered by the defendants.”

A second ballot was taken and this time it came up six for innocent and six for conviction.

Updegraff had been an abolitionist, and he was asked to explain his beliefs. He said that many of them had been Quakers and were the “most peaceable, orderly folks that could be found in any country.” He described them as “shrinking from notoriety” and were more interested in being “beloved and prized by God alone.”

After another ballot, it was nine for conviction and three for innocent. A fourth and final ballot was taken and Updegraff said it “was solid for conviction.”

Pardon from the governor

However, this conviction would not stand. The 18 men would be pardoned by then Governor David Porter. In a statement Porter wrote dated Sept. 6, 1842, he said an “itinerant lecturer came to the town of Muncy.”

The speaker’s comments were considered “pernicious to the cause of public morals, and destructive to all the cherished interests of society.” The lecture contained “equally alarming and (the) destructive doctrine of the dissolution of the Union of the States.”

At the conclusion of the incident, Updegraff referred to Porter as “Previous Pardon Porter.” Thanks to his involvement, the men were never sentenced.

However, Updegraff would go on to be remembered for his kindness and generosity.

‘Man of integrity and morality’

Hawley was not forgotten.

In the “History of Lycoming,”edited by John Megginess, Hawley was “remembered and honored” as a “man of integrity and morality.” “He was the first man in the community who had the courage to vote for the Abolition ticket.”

He was described as having the “mental make-up” of famed abolitionist John Brown. However his “sympathy with the Friends” (or Quakers) kept his views on war as “not in the same spirit aggressive” as Brown’s.

The equal temperament was one of the reasons he was appointed “postmaster of Muncy” from July 9, 1861, to March 12, 1873.