MUNCY – The mid-1770s were an untamed time for what would become Lycoming County. As the American Revolution raged, settlers were moving into this area of Central Pennsylvania. The Iroquois and Lenape tribes allied themselves with the British and regularly would attack the British enemies and those of European descent west of the Susquehanna River.

The local Native American tribes executed a group of settlers in an area that is near where the Family Dollar is located on Fourth Street.

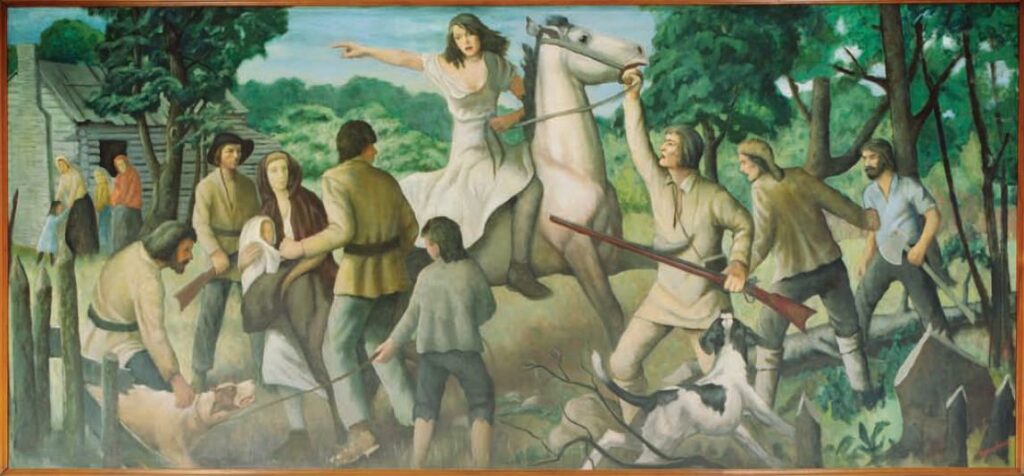

During July of 1778, the murderous rampage began to intensify and one woman would go down in Lycoming County history as a hero that saved many of those settlers in what would be known as the Big Runaway.

American history writer Tara Ross explained, “On June 10, (1778), local settlers were shaken when the Plum Tree Massacre occurred. A group of sixteen settlers was attacked by Indians. Several of the settlers, including women and children, were killed and scalped. That massacre was followed by another on July 3.”

Ross further said that the “Indians later collected monetary rewards for 227 American scalps.”

The settlers were in trouble.

According to the website entitled, “Legends of America,” “Fort Brady was a private stockade built by Captain John Brady at Muncy, in Lycoming County,”

The Luminary (of Muncy) on March 17, 1910, explained that Brady, who served in the Continental Army, had gathered his men together.

“The brave Captain Brady had the call to arms sounded, the little garrison was mustered on the parade ground, and in a few hurried sentences the events…were related, and the inevitable fate of the settlers (who had not been attacked) on Muncy Creek portrayed, if not notified at once,” the writer of the article said.

“Who will volunteer?”

It was explained that the other settlers would meet the same gruesome fate as other settlers if not warned.

Brady’s favorite horse was saddled and readied.

“Who will volunteer to carry the news of danger to our friends?” Brady asked.

The grassison remained quiet.

As if pleading, Brady said, “This very night, the wiley foe, serpent-like, will creep to their very doors, and tomorrow morning, when the first gleam of light rises over the Muncy hills, the torch will be applied to their huts, the knife will gleam in the air, and scalps will be torn from defenseless heads!”

One last time he “thundered” to his garrison “Who? Who?”

Just then, from his right, a “ gentle voice” answered.

“I, captain, l will apprise them of their danger,” a woman said. “I know the trails…well (and) I can make the circuit.”

Warning the settlers

The woman was named Rachel Silverthorn.

The Luminary writer said she “grasped the reins of the faithful animal that stood ready, like herself to be sacrificed if necessary, in the interest of humanity.”

Brady’s soldiers were gobsmacked and before they knew it, she “mounted and (was) flying with the speed of the wind to the nearest cabin on the creek.”

The Women History Blog.com explained that “Rachel returned later that night, and under the cover of darkness, every exposed settler was safely housed in the fort. “

By the morning, flames from the burning cabins could be seen all the way to Fort Brady.

“Her own family’s cabin was burned to the ground,” a writer for the Women History Blog said.

Because of her actions, the Luminary said, “the brave and beautiful Rachel Silverthorn no doubt saved some of her friends from the cruel tomahawk and scalping knife.”

It was estimated that “four-fifths of the population of the West Branch Valley deserted their homes.” The financial loss of property and the like was estimated at $200,000.

Soon the warring Native Americans would leave, and, according to the Women History Blog, “the Silverthorn family returned and erected a temporary shelter on the charred remains of their log cabin and made an effort to harvest their ripening grain fields.”

Attacks continue

However, the local tribes would continue their minor attacks as the settlers returned to the area.

The Women History Blog explained that when word reached Philadelphia, Col. Daniel Brodhead was ordered to assist the inhabitants of the area. He arrived with 125 men which established a deeper peace. Soon Col. Thomas Hartley arrived to replace Brodhead. Hartley took 200 men and raided the Native American villages and killed a local chief.

The local Indians wanted revenge on Brady – blaming him for their losses. During the winter of 1779, Brady was getting supplies for Fort Brady when he was gunned down on Wolf Run.

“Brady’s death was a serious blow to the settlers, because the Indians resumed the attacks with increased vigor,” the blog said.

In July of 1779, a force of Native Americans were armed and ready to raid Fort Brady. Thanks to the stealthy efforts of soldier Robert Covenhoven, he was able to warn the locals. At which time, General John Sullivan, who was located in Sunbury, was warned and he led an army to fight against the Indian army in what was called the Battle of Newton (which is located near Elmira, New York).

The Women History Blog said that, ”General Sullivan’s expedition gave the Indians a taste of war in their own territory.”

Native American raids would continue in the area, but the Iroquois forces would “not recover.”

While many of the men are considered heroes in their own right, Silverthorn was honored for heroism.

The Luminary said that Silverthorn’s “noble daring and loving devotion was so fondly regarded by the generations now resting in the land of silence.”