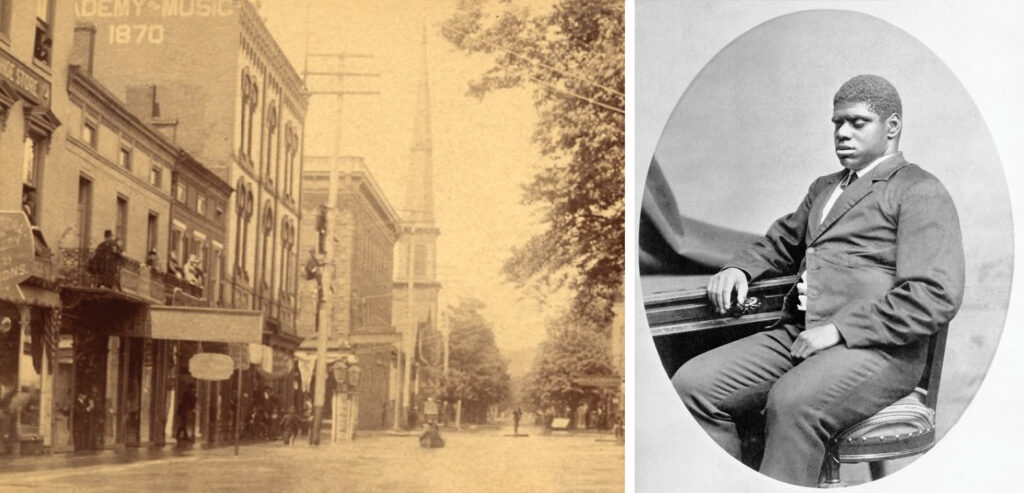

It was on Nov. 2, 1871, that a unique individual came to Williamsport to play piano at the Academy of Music that was once located at the corner of Pine and Fourth Street (near where Otto Bookstore is today). The 22 year-old musician was described by the West Branch Bulletin as “the greatest musical prodigy that the world ever saw.” Which was ironic, because he never saw anything.

His name was Thomas Wiggins and he was born blind on May 25, 1849, in Harris County, Georgia. He grew up on a plantation in Columbus, Georgia, that belonged to General James Bethune. According to “The Ballad of Blind Tom” a biography by Deirdre O’Connell, Wiggins would regularly imitate the animals that surrounded his estate.

Due to his blindness, he was not given the same responsibilities as the other slaves. He in turn would wander around the estate. He was able to repeat the exact words and sounds he heard.

O’Connell also said the Bethunes were a “musical family” that were either “instrumentalists or vocalists or both.” When he was young, Wiggins developed a friendship with the Bethune children. In 1853, the family purchased a piano. Upon hearing the instrument, Wiggins was enthralled and did everything he could to get to the instrument.

Soon he learned to play by ear and began to compose his own music based on the sounds he heard and stories told to him. In 1861, with the Civil War underway, he composed a soundtrack to the Battle of Manassas, which occurred in Prince William County, Virginia, on July 21, 1861. The piece features the melody of “Dixie” and “Yankee Doodle Dandy” clashing to mix piano bombardments representing cannon and gunfire.

Wiggins played that piece for his Williamsport audience on Nov. 2, 1871.

“His battle of Manassas … afforded much delight to the audience,” a reporter for the Daily Lycoming Gazette and West Branch Bulletin said in the Nov. 3, 1871, edition. The writer described the Academy of Music as having been “jammed … to hear that wonder musical prodigy.”

Wiggins sat behind a Steinway piano, an instrument said to be “without equal in the world.” As he played the music of “the best authors,” he did so with “remarkable force and power.” He also played a piece inspired by a thunderstorm and was “executed in an artistic manner – the deep rolling tones of the thunder were well imitated, and as the sweet melodious music floated gracefully on the air.”

“The effect was grand,” the reporter said.

As the program continued, Wiggins imitated “the guitar, banjo, music box, with amusing corrections of tone and style.”

However, what was amazing – for any time period – was Blind Tom’s ability to perform three songs at the same time. “(He) played Fisher’s Hornpipe with one hand, Yankee Doodle with the other, and sung ‘Tramp, tramp, the Boys are Marching,’ all at the same time. The expression of his efforts is powerful,” the writer said.

It was further reported, in the Nov. 3 article, that Wiggins was “strongly developed in the hands, arms and shoulders, his great nerve power drives these members with a force that is rare…He seems to throw his whole soul into the effort and his mind apparently revels in delight amid the concord of sweet sounds.”

How was he able to do all this?

In her book, O’Connell said that Wiggins’s behavior would “point, with some confidence, to Early Infantile Autism.” She said that because of his “echolia, heightened sensory discrimination and ability to recall seemingly meaningless details alerting them to the possibility of an autistic spectral disorder.” O’Connell said that his “striking lack of common sense clinching the verdict” for autism.

She further explained that due to his lack of sight, a “re-wiring of his brain” occurred and his hearing became his main source of sensory perception. The Gazette-Bulletin writer described the very characteristics of someone with autistic tendencies.

“At the conclusion of every piece he jumps up quickly and applauds himself by clapping his hands in the most enthusiastic manner. This is thought to arise from his imitating everything he hears, and being used to hearing his audience applaud,” the writer said.

During the concert, Wiggins needed an intermission of sorts.

“His nervous excitement becomes so great that he has to be taken behind the scenes and there allowed to jump around – to ‘let off steam’ as it were – and perform some lively tricks,” the reporter wrote.

In an email conversation with O’Connell, she said there is a resurgence of interest in the music of Blind Tom. She pointed to a March 3, 2021, article in the New York Times which discussed Wiggins’s life and contribution to the world of music.

“His music is performed more often — thanks in large part to (pianist) John Davis’s recordings. Critics and academics take him seriously, seeing him as a proto-modernist,” O’Connell said.

Wiggins will go down in history as a man who entertained his audience.

At the end of his concert, his audience was enthralled. Never had they seen anything like that, and thankfully, they were able to see it several more times. Blind Tom returned to the City of Williamsport several times before he died of a stroke in 1908. It seemed, each audience loved every minute of it.

“His music (was) unusually inspiring, and (it) causes almost a furore in the audience,” the writer said.