Reports of crimes against children have nearly doubled in Lycoming County over the past 10 years, according to data from the county Children and Youth Services. But the reason for this increase is complex.

“Most of the effect is that people have a higher level of awareness now,” said Psychologist Michael Gillum, who is based in Williamsport and services the Northcentral PA region. “We’re seeing more get reported.”

Gillum said that it’s not clear if the number of abuses have risen over the past 10 years, but the level of reporting has brought cases that were previously unseen, into the forefront.

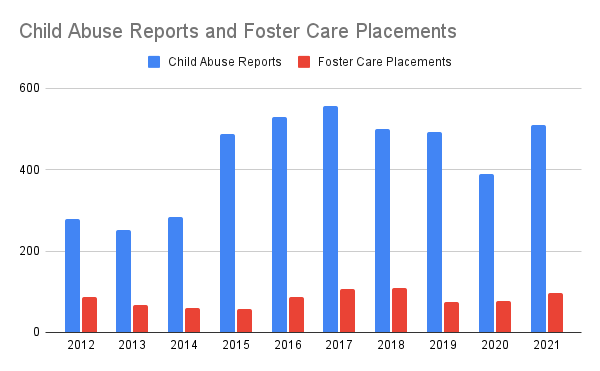

In 2012, Lycoming County received 279 child protective services reports. Over the next 10 years, that number rose to 511 abuse cases reported in 2021, according to data received after a Right to Know Request filed with Lycoming County.

Also in 2012, the number of children to enter the foster care system was 88. Over the next 10 years, the number of children in foster care has remained steady, peaking at 109 in 2018, and in 2021 there were 97 placements.

Matt Salvatori, executive director at the county Children and Youth Services, did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the rising cases’ impact on the youth services department and its staff.

Police perspective

Police departments in Lycoming County also are a rise in child abuse cases and investigations.

“Yes, unfortunately we’ve experienced an increase in crimes against children,” said Sgt. Christopher Kriner, with the Old Lycoming Police Department. “The vast majority of our sex offense cases also have child victims.”

In Old Lycoming Township, 15 abuse against children cases were investigated in 2020, 21 child abuse cases were investigated in 2021 and so far in 2022, 15 child abuse cases have been investigated, according to Kriner.

“Sticking with our multidisciplinary approach here (in Lycoming County), where police usually work hand-in-hand with CYS and other stakeholders like doctors and school counselors, is helpful,” Kriner said. “Volume of cases is definitely an issue, though.”

For the Pennsylvania State Police, a rise in child abuse cases means that more mandated reporters are speaking out, according to Trooper Sara Barrett, who is a member of the Criminal Investigation Unit in Montoursville.

“County agencies are training more individuals and bringing awareness into what to look for when working with our youth,” Barrett said.

She added that new cases often come to light years after the offense, when children have grown and decided to speak out about their experience with abuse.

“Once they are confident to talk to someone about what happened, (the state police) and any other law enforcement agency in the troop works diligently to bring some justice to the victim,” Barret said.

The state police investigate sexual allegations, physical abuse, improper schooling, lack of medical treatment, according to Barrett. She added that a lot of allegations that are seen within the troop a sexual in nature.

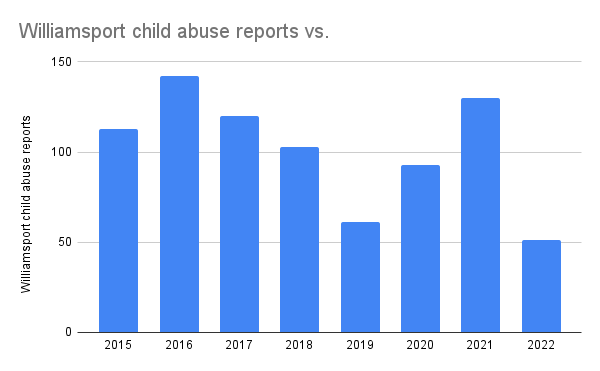

Unlike the rising numbers of the county as a whole, the Williamsport Bureau of Police have seen reports of child abuse fluctuate over the years, according to Capt. Jason Bolt, the city’s assistant police chief.

In Williamsport, there were 113 child abuse reports in 2015, according to Bolt. Since 2015, the number of abuse reports have peaked at 142 in 2016 and ended at 130 in 2021. As of mid-June, 51 child abuse cases were reported in 2022.

According to Bolt, a number of the city’s abuse cases involving children deal with sexual abuse by a friend or relative.

Sexual abuse

The prevelence of sexual abuse cases among children is evident, according to Gillum, who said that it makes up the highest percentage of cases that come into his office.

“There is this intense culture shift in the United States where all of a sudden people are much more aware of abuse cases in general … especially with sexual abuse,” he said.

Gillum works directly with children through his practice as well as school programs and contract work with children and youth services in various counties including Tioga, Sullivan Bradford and Snyder. Gillum hasn’t worked with the Lycoming County Children and Youth in over 12 years, he said.

For Gillum, it’s difficult to talk about the rise in sexual abuse cases without also highlighting the region’s drug problem.

“I almost never get a case where the perpetrator doesn’t have a serious drug addiction,” he said. “When I evaluate them, they will blame it on the drugs.”

Gillum continued. “People who are inclined to sexually abuse children,… their inhebitions melt away with drugs and alcohol.”

Through his nonprofit The Silent No More Foundation, Gillum works to educate the public about the prevalence of sexual abuse among children as well as taking proactive measures to bring foward evidence and witnesses against abusers.

Limitations to the system

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the limitations to helping child victims of abuse was a lack of access. Schools were shut down and public gatherings drastically limited. This resulted in fewer abuses reported among children; however, reports spiked again the following year.

During this time of low abuse reports, Gillum said the rate of abuse increased, primarily due to the isolation of the pandemic and the increased proximity between victims and their abusers.

“I think a lot of abuse went unchecked over the past two years,” Gillum said. “Now we are getting a big increase in reports.”

Abuse reports jumped back up above 500 the following year, according to the county’s data.

For the state police, Barrett said the biggest limitation is cooperation in investigations.

“Victims oftentimes do not want to relive the trauma or just are not ready to tell us,” Barrett said. “If we have very young victims … they don’t know how to verbally express what happened to them. We rely on forensic interviewers to assist in interviewing our juvenile victims.”

Child victims often will not report a crime until they are older and feel comfortable disclosing their traumatic past, Barrett added.

The rise in cases over the past 10 years have also put a strain on children and youth services, according to Gillum.

“Children and youth agencies are at a point where they are starting to get overwhelmed with dealing with all the cases that are coming at them,” he said. Staffing shortages continue to be a problem for many agencies, but Gillum said for agencies responsible for the wellbeing of children, it is an even more dire issue.

Gillum encouraged members of the public to continue to be on the lookout for possible abuse of children, stressing the importance of becoming more educated about the process of reporting abuse and making a report when something seems wrong.

“These kids can be saved, but people have to speak up,” Gillum said. “It is our business if it’s a child.”