It’s 1918. A young girl leaves her home and walks down Mulberry Street in Williamsport. She crosses the railroad tracks toward the platform and sees wooden crates loaded four high as far as she can see. Inside of each is the body of a soldier killed by the Spanish flu and sent home.

When the girl grew up she told the story to Dr. John Piper, historian and professor at Lycoming College. She is no longer living, but Piper has never forgotten the story.

Senior citizens today may have a family member or friend who was killed by the disease. Piper’s grandmother died of influenza at age 30 and his uncle died at age 2.

“If you got it, the chances were very good that you were not going to survive it,” Piper said.

The mortality rate of the 1918 influenza was highest among children younger than 5, 20 to 40 year old and those over 65.

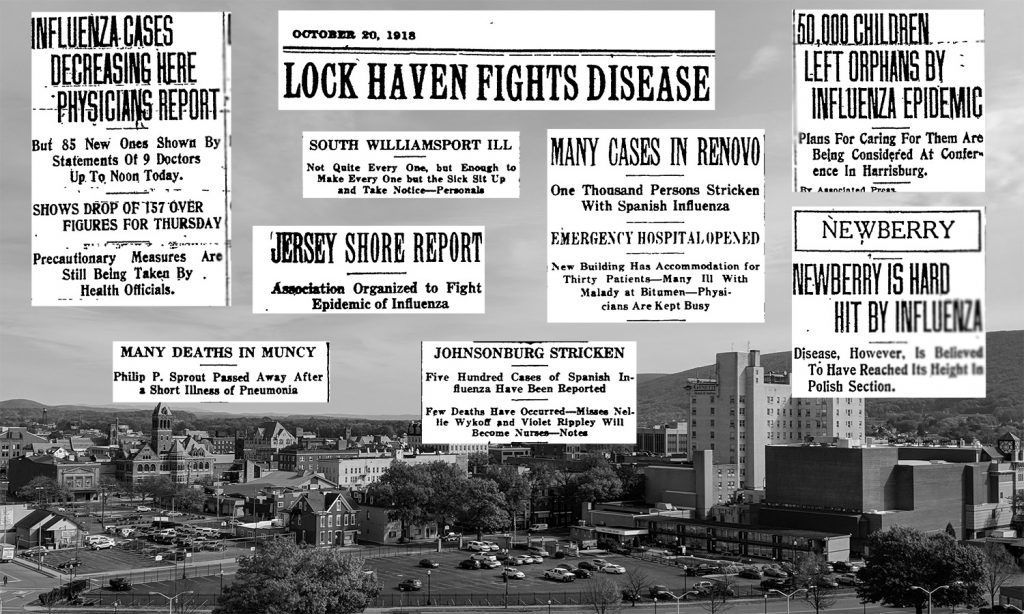

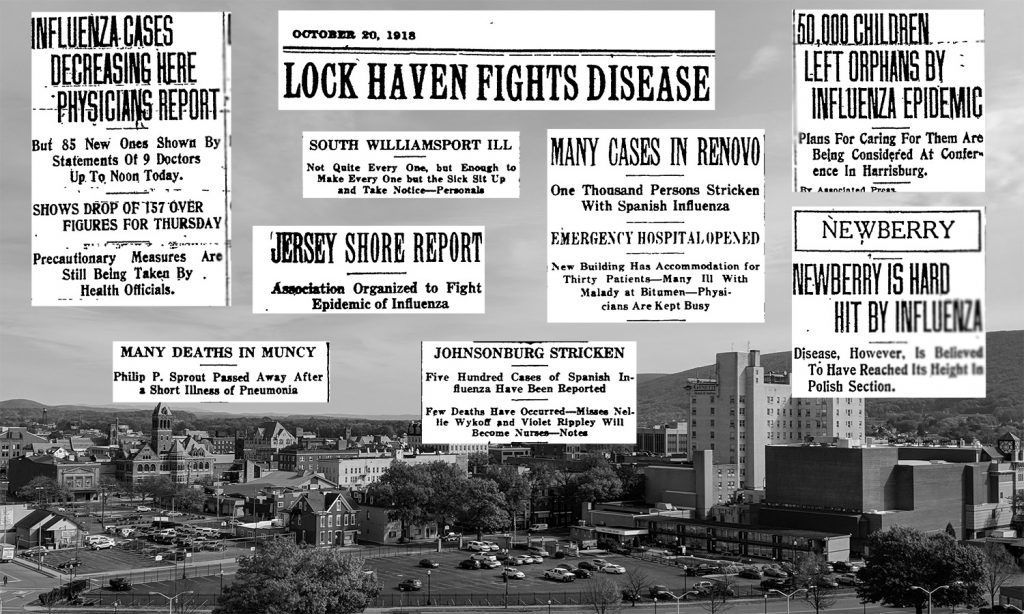

Filling the headlines

In some stark similarities to the present pandemic, newspapers were filled with case counts, records of the dead and quarantine measures.

Hitting its peak toward the end of World War I, cases of the 1918 influenza pandemic, or Spanish flu, began increasing in Lycoming County and the surrounding region in August, but didn’t spike until October and November.

The origin of the Spanish flu isn’t known, according to Piper. It was given the Spanish qualifier because of how virulent the cases in Spain were, he said.

The virus spread through Europe and then the rest of the world at record pace with over 500 million cases and as many as 50 million deaths, 625,000 recorded in the United States. It remains the deadliest pandemic in history.

The infections began among soldiers in the spring. Cases in military camps skyrocketed. Eventually many camps were closed and the soldiers were sent home, according to Piper.

“The downside was everyone with the disease took it to their homes,” he said, “many of them rural, small-town folks.”

Local region devastated

In early October, headlines in the Williamsport Sun and the Grit – the area’s local news outlets at the time – began to fill with news of the pandemic.

In less than two weeks, local hospitals were overrun as hundreds of new cases were reported each day in Williamsport. Other local towns like Renovo, Emporium and Saint Mary’s went on lockdown, opening new facilities to house patients and sometimes using church basements.

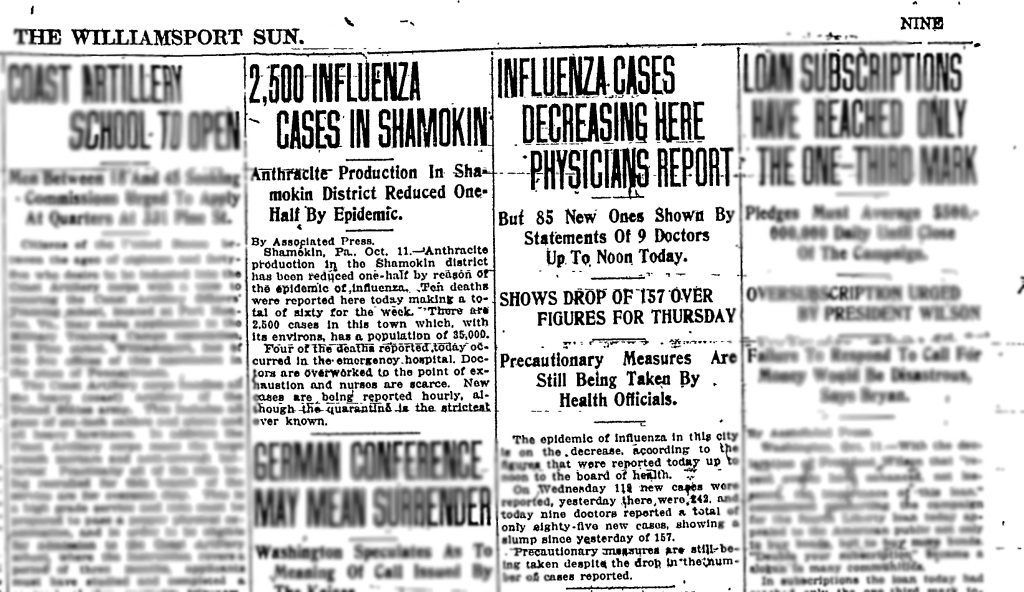

By Oct. 11, 1918, cases in Williamsport began to decrease below 100 per day. But on the same day, 2,500 cases were reported in Shamokin, which had a population of 35,000 at the time.

On Oct. 20, over 200 cases were reported in South Williamsport, enough to “make every one but the sick sit up and take notice,” the Grit headline quipped.

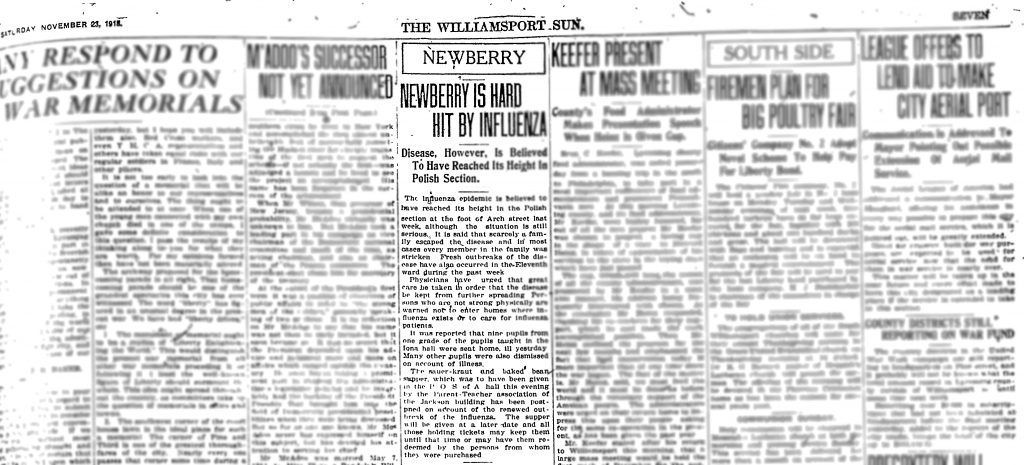

Newberry was hit hard by the virus. A Nov. 23 report in the Williamsport Sun showed that the Polish section, at the base of Arch Street, was affected the most.

“It is said that scarcely a family escaped the disease and in most cases every member of the family was stricken,” stated the Sun’s report. While the virus was said to be weakening by this time, reports of fresh cases continued to appear.

“Physicians have urged that great care be taken in order that the disease be kept from further spreading. Persons who are not strong physically are warned not to enter homes where influenza exists or to care for influenza patients.”

In each daily or weekly newspaper, the names of those who were ill or sick were published. An overrun Lock Haven sent out calls for more nurses. In Jersey Shore, an emergency aid organization was formed to work with the state health officials to combat the virus.

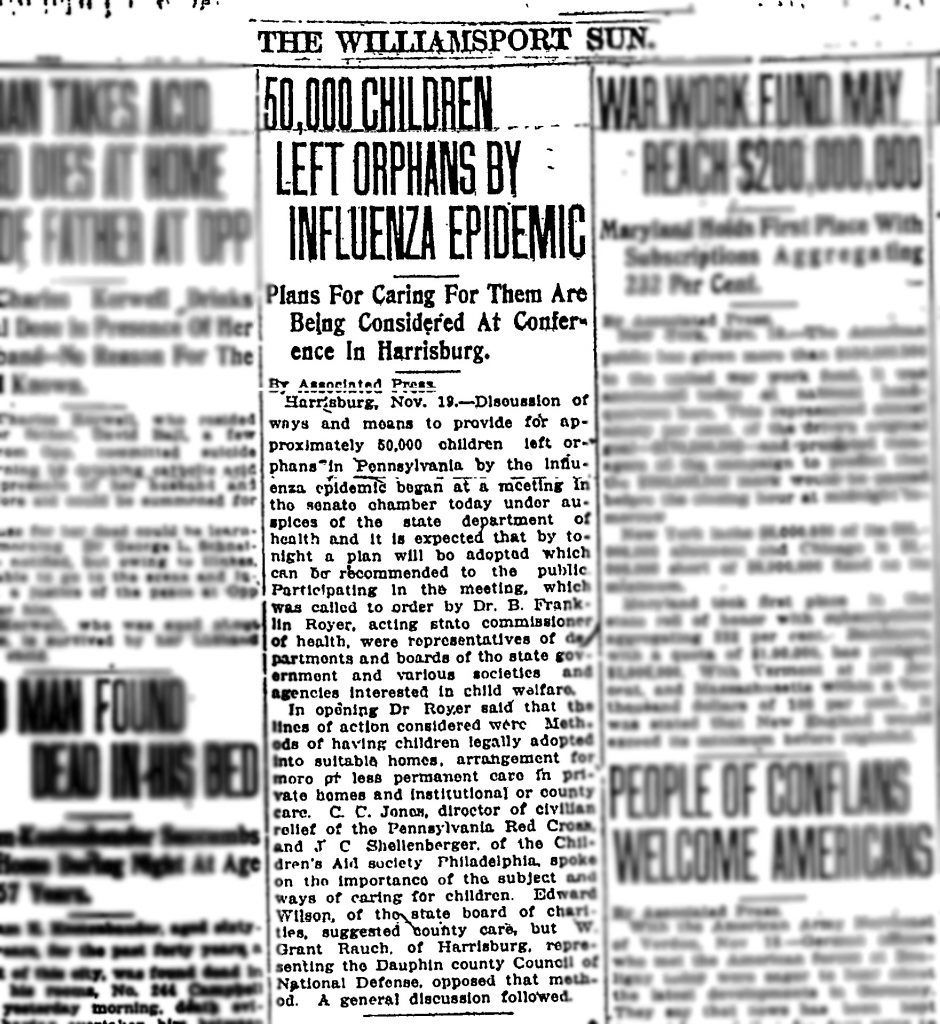

Statewide, over 50,000 children were left orphaned.

Businesses shutdown

Not unlike today, businesses were not untouched by the pandemic. Bars and hotels were closed for at least two months throughout the state. Over 700 Pennsylvania Railroad employees were reported off duty due to the influenza. Coal production also decreased across the country.

An order from the Pennsylvania governor closed all education institutions in the state, according to Piper. The Williamsport Dickinson Seminary, which today is Lycoming College, was closed from August to October, Piper said.

The business closures did not come without some controversy. An Oct. 24 report in the Williamsport Sun, shows that the police raided the Shiner hotel at 202 Market St. after officers saw a man exit with a bottle of alcohol.

“The proprietor and his wife and the bartender all acknowledged that they had been selling, despite the quarantine placed upon all kinds of sales by hotels”

While the matter seemed to be taken seriously by the police, it was not made clear what the punishment against the establishment was, simply that “in all probability, action would be taken against Lingemann (the owner) at once.”

In Lock Haven, controversy about the city’s handling of the pandemic was unmistakable, pointing to some requirements mandated by the Board of Health that were not carried out.

A full excerpt from the Grit’s Nov. 3, 1918, issue:

“Sentiment in this city (Lock Haven) is almost unanimous that far better results would have been obtained in preventing the spread of the influenza by quarantining and placarding homes where cases of the malady existed than by closing all public places. The Board of Health decided to quarantine every home where a case of the disease existed. A large number of quarantine cards were printed, but when Health Officer McNaul started out to begin his big job, he found some of the physicians reluctant to give the names of their patients who were ill with the malady because the regulations of the State Board of Health did not require it, while others declared they were so busy they did not have the necessary time to provide the names of the influenza patients. Hence the quarantine plan was abandoned. While all the saloons have been closed for a months now, the proprietors, as well as the wholesalers, have been permitted to sell limited quantities of whisky or brandy for use in homes where cases of influenza existed and they have been doing so although the barrooms have been closed and no persons were allowed to congregate there.”

Moving forward

By November headlines were full of reassurance, saying the pandemic was weakening, case numbers were decreasing, businesses and towns were opening up again.

Seemingly, just as quickly as the horror had arrived, it was gone. No vaccine was ever found. On Nov. 11, 1918, World War I ended. But while over 53,000 soldiers died fighting the Germans, over 45,000 died of the Spanish flu. In total, deaths from the Great War numbered nearly 2 million, but global deaths from the pandemic reached as high as 50 million.

The total number of deaths in this area is not clear, but one thing is certain: The virus’ impact was severe. While few, if any, are alive to remember it, historians like Piper will always recall stories like the little girl who walked down Mulberry Street to see the crates.