Imagine being trapped in your vehicle after a brutal crash, shattered glass strewn around, pain and confusion clouding your senses, the wail of sirens growing louder as first responders try to safely traverse icy roads to reach the scene in time.

One medical response team doesn’t need to worry about road conditions and their potential to adversely affect response time.

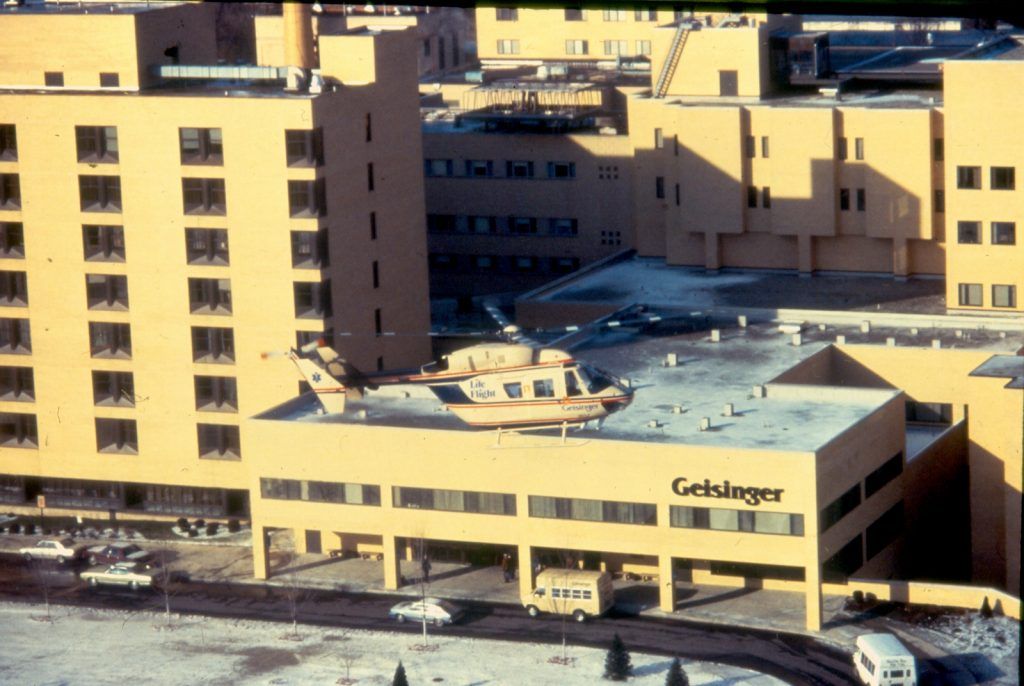

Geisinger Life Flight’s fleet of medical helicopters celebrates its 39th anniversary this July.

Team effort

“We started with one French helicopter,” said Jim Smith, the now-retired vice president of administration who was part of the team that conceived of the idea of an air response and retrieval unit for the medical center.

Bearing the nickname “the pregnant guppy,” this model helicopter was “not streamlined,” Jim said. Its passenger area stretched about 6-foot-2 across, “so patients could go straight in.”

At first, Geisinger rented the aircraft from Evergreen Helicopters, an operator based in Oregon. In 1983, two years into the Life Flight program, Geisinger bought its first twin-engine helicopter, a model BK117 that cost about $927,000.

Geisinger now has nine helicopters in its hangars, but they are much different than their predecessor. The Eurocopter model 145 is a twin-engine bird that can be operated by one pilot using instruments. The price tag is $7.2 million each.

“They are more technically sophisticated,” Jim said. “It’s totally different now.”

‘A better way’

Instituting a medical helicopter service at Geisinger sprang not from a desire to bring more revenue into the medical center but rather from a need to help improve the littlest patients’ access to lifesaving medical care.

In 1973, the Bush Pavilion at Geisinger opened with a sixth-floor pediatrics unit and an emergency department at ground level. Dr. Tom Royer was named the director of emergency medicine and of the new ER.

The following year, Dr. Tom Martin, who was in charge of the pediatrics department, reached out to Jim.

“We have a wonderful new NICU with capacity for 11 very sick babies,” Martin told Jim, referring to Geisinger’s neonatal intensive care unit.

He estimated that about 3% of the 350 or so babies born or cared for at Geisinger would “be in trouble and need care in this new unit.”

“We need a way to go out in the region and get the sick babies being born out there and get them safely back to our unit,” Martin added.

Jim and his team set to work, outfitting one of the Danville Ambulance Service’s van-type ambulances with a portable incubator that was self-contained and able to control heat, oxygen and humidity levels to provide a safe environment for premature or low-weight newborns. The team modified an adult respirator to fit their needs and added a power supply for the equipment that would keep infants alive until they could be treated within the confines of the NICU.

Jim, an emergency medical technician involved with the Danville Ambulance Service, often drove the “baby buggy,” officially known as the hospital’s neonatal retrieval unit, and was accompanied by Martin, the doctor in charge. The unit began tending to infants’ needs on July 1, 1974.

“This program was the very first time that any service of GMC had ‘gone out’ to serve others in the region,” Jim wrote in a historical account titled “The Early Days of Geisinger Life Flight.”

Within five years, the neonatal retrieval unit was shuttling more than 300 babies a year.

“They just couldn’t keep up,” Jim said of the driver and doctor in charge. “They were still all volunteers … and there were an awful lot of midnight runs.”

The team realized the time had come to implement a change when, in the winter of 1980, a terrible storm heaped snow on the area, rendering the roads impassable. It was the worst possible time for anyone to need to travel and, of course, that’s just what doctors at a Scranton hospital needed.

“A desperate call came … to get a critically ill newborn to Danville,” Jim wrote. “We needed to get the NICU team to Scranton, to stabilize the tiny infant, and then get them all back to Danville.”

He and Royer enlisted the help of the state police, which had a force of helicopters.

“The state police — god love them — had these little Bell Jet Rangers,” Jim said. “They were the right size to go up and look around, maybe chase a car down the road, but they were narrow.”

They also were too small to carry both the neonatal team and their equipment, so two choppers set out for Scranton.

But there still was a problem. The Rangers couldn’t fly at night. They wouldn’t be able to return the baby, the team or the equipment to Danville. So, despite the inclement weather, the team equipped an ambulance with tire chains and proceeded to complete the dangerous journey many hours later.

As the second police helicopter took flight, Royer and Jim “standing in the parking lot in the swirling snow, looked at each other and declared, ‘There’s gotta be a better way,’ ” Jim wrote in his history chronicle.

‘A part of our lives’

Twelve to 18 months after that blizzard, things were better — strikingly so. Jim and his team rallied in that time frame to complete all of the research, legwork, education and problem-solving for Geisinger to implement its own helicopter program.

“We ran all over the country and visited programs that were already operating,” Jim said. “The people were very willing to share with us.”

The Hermann Hospital in Houston, Texas, even agreed to share the name it already had in place for its helicopter program — Life Flight.

“We got permission from them to use the name they had trademarked,” Jim said. “Even now, on our helicopters, there’s a little red heart over the ‘I’ … and many programs use that now.”

Back in Danville, “We had to put together the communications room, build a hangar, put a fuel tank in the ground … it was a lot. But we pushed and pushed and we made it happen.”

On July 1, 1981, the first Geisinger Life Flight helicopter turned its rotors and rose into the sky on its first official flight. Kathy McGann was seated as the first flight nurse. Several years later, McGann met and married Jim Smith.

The couple’s home in Danville is “literally on the flight path,” Jim said. “It’s been a part of our life” and remains so though they both are retired.

At its inception, Life Flight was projected to make 150 flights a year. The actual number was closer to 350. Now, it’s around 3,500 a year — and about 70,000 flights throughout its existence.

‘We didn’t have to fight traffic’

Early on, Life Flight’s regular crew consisted of a pilot, a physician and a nurse, Jim said. “Now it’s a nurse and a paramedic, usually.”

A registered nurse, Kathy worked at Geisinger as a cardiac intensive care nurse before moving into the Life Flight program. She joined six other flight nurses who brought a mix of skills and concentrations into the program.

She spent three years as a flight nurse and flew on 350 flights.

“I was 29 at the time,” said Kathy, who looked forward to the new experience. “It was interesting. We didn’t have to fight traffic!”

Flight in a helicopter is much different than traveling in a plane.

“It was nothing like a jet. We didn’t go as high and didn’t have to worry about being in a pressurized cabin,” Kathy said. “I much prefer riding in a helicopter.”

Throughout the years, Geisinger Life Flight has emphasized safety.

“In the early summer of ’81, the pilots took the staff up to familiarize them” with the helicopter and its movements, such as banking, landing and landing without an engine. “We went through all of that so the staff felt comfortable that this was done very professionally,” Jim said.

While Kathy tended to patients onboard the helicopter, Jim only traveled in it for “(public relations) flights” designed to bring attention to the program and show people how the endeavor worked.

“I went all over the region to show fire companies and all of the hospitals in 24 counties how it works. We wanted to make sure we knew where we would land if we were called to one of these hospitals,” he said. “But sometimes PR flights turned into patient flights. We never flew anywhere without the physician and the flight nurse.”

One such instance occurred in Williamsport. Jim was in town to show the helicopter to administrators at the city hospital when the county dispatch contacted the pilot and asked for the medical team’s help.

A tractor-trailer had rolled over on Route 15 near Trout Run and the driver was trapped inside.

The helicopter, which had left Jim at the Williamsport Hospital, returned to that site to offload the patient and also was able to pick up Jim for the return flight to Danville.

“That was neat. It proved our point that Life Flight would be able to bring patients to the appropriate hospital, not necessarily back to Geisinger,” Jim said.

‘Golden hour’

Life Flight has made a “major difference” to the people who find themselves in dire need of emergency medical care, Jim said, making note of “the golden hour,” a term given to the first 60 minutes following the occurrence of a traumatic injury.

Medical treatment — or the lack of it — during that “first hour made a major difference,” he said. “Getting a doctor and a trauma nurse to the patient … that was the big factor … bringing definitive care to the patient.”

On scene, the Life Flight crew works to introduce primary medical care and stabilize patients for transport. At one particular crash on Interstate 80 in Centre County, Kathy arrived to find a tractor-trailer upside down, its driver trapped in the wreckage.

“His blood pressure was low and dropping. He was going into shock,” she said, referring to a state the human body deteriorates to when enough oxygen is not getting to the brain and other vital organs like the heart and kidneys. “It’s usually because they are bleeding profusely — hemorrhaging — somewhere. Sometimes you can see it and sometimes you can’t.”

Kathy entered the crushed cab to better assist the driver.

“The firefighters made me put their turnout gear on, their coat and hat,” she recalled. “I started an IV to provide fluids and stabilized him, using MAST trousers to help support his blood pressure.”

Every patient was different, Kathy said, but the team worked hard to provide whatever medical treatment was needed in the field and during the trip to a medical center.

“Geisinger is pretty much in the middle of nowhere. If you could get from Geisinger to Clearfield in 40 minutes instead of a couple of hours, it could make a major difference,” Jim said. “There are an awful lot of people who are alive today who wouldn’t be without Life Flight.”

I was a premature infant flown from Pocono to Danville within the first two weeks of service. I am now an overgrown Paramedic and think of Life Flight every time I work with Aeromedical, because of not for them, I would not be here to have the job I do. I’ve always wished I could find the crew but never really thought it was still possible. Thank you all!